To celebrate the summer of 2017, we are pleased to present an ongoing series of reading recommendations/reminiscences by Goose Lane authors past and present.

Today: Michelle Butler Hallett (This Marlowe)

An eye to summer reading

One glimpse at Anton's eyes, and I fell in love. That's all it took. I knew him only by reputation; his eyes worked the rest — intrigued me, charmed me. Of course, I'm married, and he's, well, dead, so no tryst. Still, the eyes of Dr Anton Pavlovich Chekhov: concern, fatigue, compassion, and pain glimmer there.

One would hope to find such eyes on a doctor, as well as on a playwright and story writer.

I picked up About Love, the Biblioasis collection of three Chekhov stories, translated by David Helwig, and designed and illustrated by Seth, back in May. The three collected stories are "A Man in a Shell," "Gooseberries," and "About Love." Love, love, love ... and unreliable narrators. Anton Chekhov misses nothing about how humans behave, and he allows his characters the space and voice to reveal themselves, often when they think they are revealing something about someone else. It's fine and delicate work, yet also honest and robust — and very moving.

I picked up About Love, the Biblioasis collection of three Chekhov stories, translated by David Helwig, and designed and illustrated by Seth, back in May. The three collected stories are "A Man in a Shell," "Gooseberries," and "About Love." Love, love, love ... and unreliable narrators. Anton Chekhov misses nothing about how humans behave, and he allows his characters the space and voice to reveal themselves, often when they think they are revealing something about someone else. It's fine and delicate work, yet also honest and robust — and very moving.

I'm now studying more of Chekhov's stories in another collection, the 1947 Viking Portable Chekhov, translated by Avrahm Yarmolinsky. The cover of this battered old paperback shows a pen-and-ink caricature of Chekhov: long and narrow face, piercing eyes, furrowed brow, subtle scowl. I don't like this image, never did, and yes, it put me off reading the work. He looks so damn stern, even judgmental, and I find the writers whose work I enjoy least are the ones who seem to judge their characters.

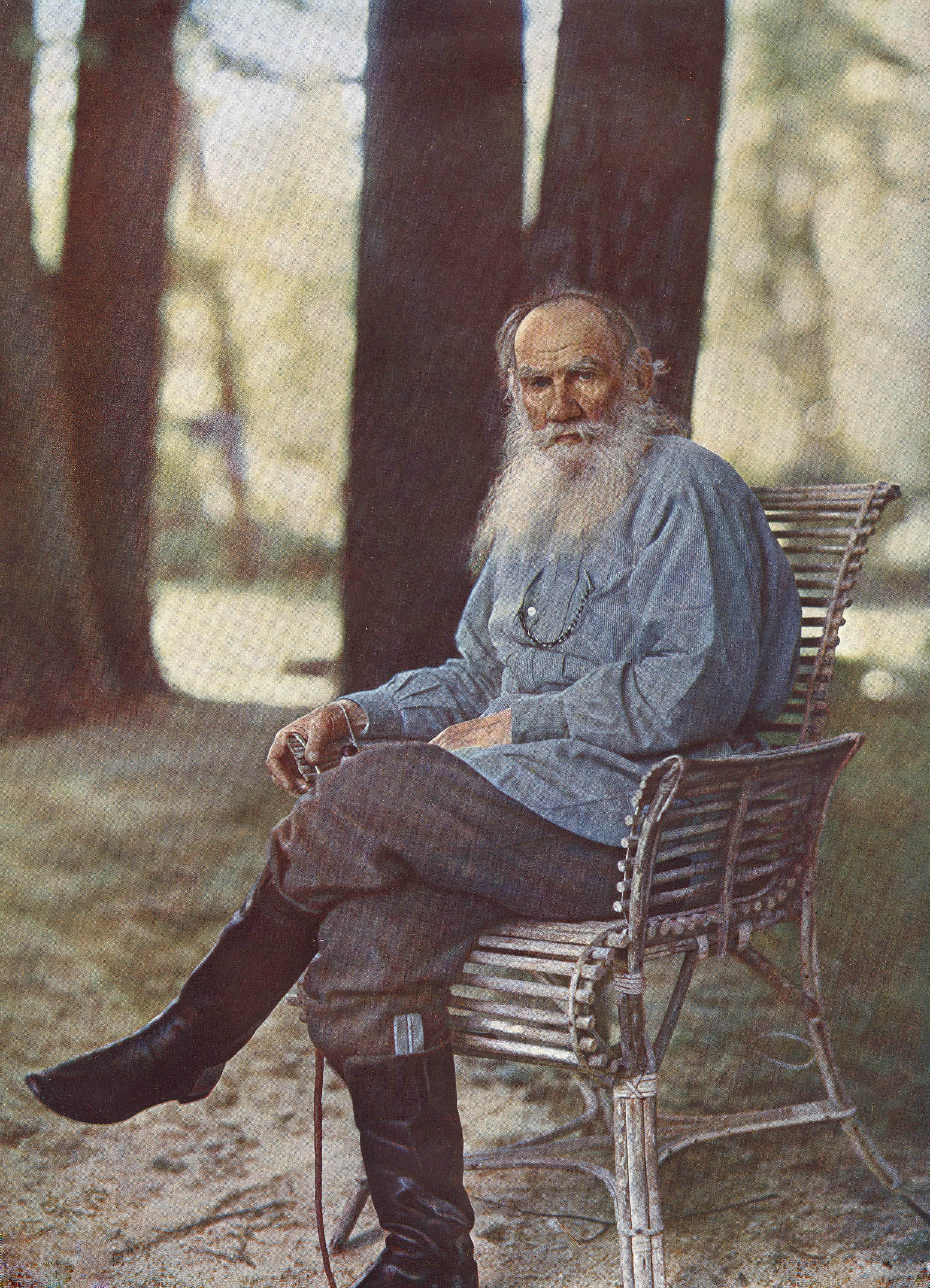

This brings me to a recent failure on my part: Leo Tolstoy. Oh, God, Tolstoy. Last winter I picked up War and Peace, again, as One of Those Books I've Always Meant to Read, and, worse, One of Those Books I Really Should Read. What a terrible way to approach someone's work: get this chore done. Oh, I found Tolstoy a chore. Maybe it's the translation. I liked some of his short stories, which I read years ago, but — and this should have warned me — I could not remember a single title, nor a character name. No, not even Ivan Ilyich. Huh, I thought, I'm getting slack. I made three false starts on War and Peace,and the novel does, to be fair, need long and uninterrupted bouts. I blamed illness for my inability to get past page 50. Sure. That's why Tolstoy kept bopping me in the face as I fell asleep and lost my grip on the book.

This brings me to a recent failure on my part: Leo Tolstoy. Oh, God, Tolstoy. Last winter I picked up War and Peace, again, as One of Those Books I've Always Meant to Read, and, worse, One of Those Books I Really Should Read. What a terrible way to approach someone's work: get this chore done. Oh, I found Tolstoy a chore. Maybe it's the translation. I liked some of his short stories, which I read years ago, but — and this should have warned me — I could not remember a single title, nor a character name. No, not even Ivan Ilyich. Huh, I thought, I'm getting slack. I made three false starts on War and Peace,and the novel does, to be fair, need long and uninterrupted bouts. I blamed illness for my inability to get past page 50. Sure. That's why Tolstoy kept bopping me in the face as I fell asleep and lost my grip on the book.

"Bouts." Reading Tolstoy felt like a fight. It took me a while to figure out why. I felt from the start that Tolstoy is judging his characters, that he pretends to weep when in fact he's just shaking his head and confiding in the ceiling, some long-bearded Puck: What fools these mortals be. Perhaps I'm wrong. Perhaps I'm just too stunned to get Tolstoy. What I do know for sure: I feel none of that judgement in Chekhov's work.

So this summer I'm reading Chekhov, not Tolstoy.

Perhaps never Tolstoy.

British novelist Anthony Powell, while spared the awkward burden of me and my crushes, also had lovely eyes: deep-set in his head, beneath a fairly heavy brow, curious, melancholy, and kind. His fiction shows those qualities, too. My husband once read aloud to me Powell's twelve-volume cycle A Dance to the Music of Time, and a few weeks ago, working through a bereavement, I watched the 1997 television adaptation. It's very good, in places excellent. Simon Russell Beale hit a career height as Kenneth Widmerpool.

British novelist Anthony Powell, while spared the awkward burden of me and my crushes, also had lovely eyes: deep-set in his head, beneath a fairly heavy brow, curious, melancholy, and kind. His fiction shows those qualities, too. My husband once read aloud to me Powell's twelve-volume cycle A Dance to the Music of Time, and a few weeks ago, working through a bereavement, I watched the 1997 television adaptation. It's very good, in places excellent. Simon Russell Beale hit a career height as Kenneth Widmerpool.

So now I want to read Powell's novels again. I often re-read books in summer. Powell's first-person narrator, Nick Jenkins, becomes less and less important as the novels progress. One might expect him to be the protagonist, or at least the main character. He's neither. He becomes the window through which we see other characters grow, fight, hate, love, and die, even as he himself grows, fights, hates, and loves. Nick reveals himself the way Chekhov's first-person narrators do: often unaware. Such technique demands great skill and, rarer still, honesty from the writer. The TV miniseries, constrained by its own dance of time, omits much. The novels lie ready, rich, and, despite a distinctly understated (and, I would argue, very twentieth-century British) tone, strange. I can learn a lot about how novels work by re-reading Anthony Powell.

So long as I'm re-reading: over there, all peacock feathers and cat's-eye glasses, leaning on her crutches, face shaded by a floppy hat as she avoids the sun, the Abbess of Andalusia, Flannery O'Connor. Like Chekhov and Powell, O'Connor writes with vigour, and an often distressing honesty about how humans behave. She is also tuned to something else: the violence of grace. Only through grace, O'Connor believes, can we grow: "All human nature vigorously resists grace because grade changes us and the change is painful."

So long as I'm re-reading: over there, all peacock feathers and cat's-eye glasses, leaning on her crutches, face shaded by a floppy hat as she avoids the sun, the Abbess of Andalusia, Flannery O'Connor. Like Chekhov and Powell, O'Connor writes with vigour, and an often distressing honesty about how humans behave. She is also tuned to something else: the violence of grace. Only through grace, O'Connor believes, can we grow: "All human nature vigorously resists grace because grade changes us and the change is painful."

I find this idea explosive. Faith, a topic most unfashionable in Canada's fiction, or so it seems to me, runs through O'Connor's work like a backbone. It's a hard faith — hard to take, and hard won. God and His grace, as she understands them, are very present in her stories and novels, and they usually appear in forms and ways the characters often fear and shun. Hazel Motes in Wise Blood and Mrs McIntyre in "The Displaced Person" might be the most blatant examples.

O'Connor refuses to play nice, something which is still expected of her as a woman writer. Even as she shows grace as something terrible and frightening in "An Enduring Chill," "A Good Man is Hard to Find," and "Revelations," she also shows evil at work, or, as she put it in a letter, Satan himself walking the earth. My summary makes her work and her struggles with faith sound simplistic; they are not. And for all of that, I do not find in O'Connor something that others complain of: that sense of judgement. Like Chekov and Powell, she presents her characters as nuanced and complex human beings. In a lovely and endearing touch, the characters who seem to most resemble O'Connor herself — the girl in "A Temple of the Holy Ghost" and Hulga (formerly Joy) Hopewell in "Good Country People" — live far from the state of The Likeable Character.

A few months ago, I came across one of those Great Writers to Read Before You Die lists — as opposed to after you die, I suppose — and found Flannery O'Connor there, along with comment on photo of her, something like "Here she is, judging her characters" The photo in question — O'Connor with a puffy face and thinning hair — was taken after a bad flare of her lupus, the disease which would kill her. The photo shows the face of a someone just out of bed and bloated with ACTH, a forerunner of prednisone, of someone who's just lost much of her hair. To me, O'Connor here looks not like a judge but a patient. She and Chekhov might have understood each other. Perhaps not: Chekhov never acknowledged his own terminal illness. Yet, to be fair to the person who captioned the photo of O'Connor and called her judgemental: yes, something uncompromising there, something devoted, flawed — and vulnerable.

It's rare.

Or perhaps I think too much about eyes.

-end-

Michelle Butler Hallett refuses to apologize for breaching imposed genre and gender boundaries. She is the author of the novels This Marlowe, deluded your sailors, Sky Waves, and Double-blind, and the story collection The shadow side of grace. Her short stories are widely anthologized: The Vagrant Revue of New Fiction, Hard Ol’ Spot, Running the Whale’s Back, Everything Is So Political, and Best American Mystery Stories 2014.

Michelle Butler Hallett refuses to apologize for breaching imposed genre and gender boundaries. She is the author of the novels This Marlowe, deluded your sailors, Sky Waves, and Double-blind, and the story collection The shadow side of grace. Her short stories are widely anthologized: The Vagrant Revue of New Fiction, Hard Ol’ Spot, Running the Whale’s Back, Everything Is So Political, and Best American Mystery Stories 2014.